When Julie Dempsey was invited to give evidence at the 2019 Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, she felt compelled to be involved. Her experience with the system has been both as a service provider and a patient – giving her acute insights into where the system is broken, and how it can be fixed.

“I’ve been around for a long time, and that’s why I was thrilled to give evidence,” she says of her deeply personal testimony. “I was hoping my experiences – which are the foundation of all the work I do – would be valuable.”

Today, Dempsey works at Forensicare as a consumer consultant representing patients’ needs. She says the wider system needs an overhaul, to move away from a medical-based hierarchy to one that puts the patient, as an individual, at the centre of all decisions, and offers peer support.

Radical change needed

At one low point, she was transported from a hospital emergency department to a psychiatric unit in a police van – she wasn’t violent or agitated, just in need of treatment. She still doesn’t understand why she had to suffer the humiliation of being bustled into a police van in public.

“The time for Band-Aid solutions is over. We need radical change.”

Dempsey’s story with the mental health system began in 1982 when, aged 21, the talented university student was hospitalised after a psychotic breakdown. “Doped up” on medication, her ambitions “crumbled” around her as she endured nearly two decades of “dehumanising” treatment that made her feel disempowered, vulnerable and suicidal: “Totally degraded ... like I was invisible and did not matter.”

At one low point, she was transported from a hospital emergency department to a psychiatric unit in a police van – she wasn’t violent or agitated, just in need of treatment. She still doesn’t understand why she had to suffer the humiliation of being bustled into a police van in public.

“That was the day I lost my sense of citizenship,” she says. “And then you cease to function as a normal human being, sharing society with other people. You’re in this subculture of subhuman, non-citizen, stigmatised people. You don’t see yourself as a person, you’re just a problem to be dealt with.”

But Dempsey says her story, while personal, is universal. “We all have slightly different experiences, but this is what happens,” she says. “My story is not a standout as something really atrocious that only happened once in the system.”

Fighter for hope

Dempsey eventually found her way out of despair after being persuaded by her case manager, on the strength of her academic background, to join the Consumer Advisory Group at NorthWestern Mental Health.

"All of a sudden it felt like there was some purpose to everything I’d been through. I could use it in a positive way, and that was really empowering.”

The role, she says, forced her to look outside her internal world to others’ circumstances. It tapped into a deep-seated aspect of her nature to fight for social justice – a characteristic that can be traced to her schooldays and her campaign to allow girls to take woodwork instead of cookery. “I was always stirring the pot a bit, I guess,” she says.

Her involvement in the advisory group led to an invitation to speak of her experiences at the Women’s Mental Health Network Victoria, whose support became instrumental in building her confidence, as her advice from a consumer perspective was increasingly sought from politicians and mental health experts.

“All of a sudden it felt like there was some purpose to everything I’d been through. I could use it in a positive way, and that was really empowering,” says Dempsey.

Finding this purpose – “standing up for human rights” – was the key to her recovery, and an example of a patient-centred approach, where treatment is tailored to people.

“Personal recovery is looking at the consumer’s strengths, and how they can use that to progress and have a meaningful life, based on what is meaningful for them,” she says. “Mental health is about someone’s mind, which makes up who they are as a person, so it’s individual for everyone.”

While medication has an important part to play, she says the current system, with its medical-based approach to “fix people”, needs to be reshaped to help people evolve as they live with mental illness. Personal recovery isn’t necessarily symptom-free, she says. “I’m not symptom-free. I still get unwell at times, but I wouldn't say I haven’t achieved things.”

Voice of experience

Dempsey hopes her testimony will help spur change through the royal commission, due to report early 2021. She highlighted a number of practical improvements for consumers, including purpose-built women-only facilities and treatment units near parks and gardens, detached from hospitals.

Introducing more peer workers, who have experienced mental illness themselves and therefore “get it”, to work one-on-one with patients as mentors and to provide hope, is also important, she says.

Meanwhile, Dempsey is improving outcomes on a daily basis at a practical and policy level. At Forensicare, in the Thomas Embling Hospital, she advocates for patients to ensure they have a say in their treatment and environment. This involves everything from ensuring adequate sunshade to providing a consumer perspective regarding the use of specialist seclusion and restraint staff.

Liaising between consumers and management is a role that requires great diplomacy, and Dempsey’s expertise was recognised in 2019 with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) Meritorious Service Award “for her skillful operation in a demanding space between service users and service providers, and her commitment to improving forensic consumer care”.

It’s demanding work, and not without personal cost. Consumer workers essentially “professionalise their lived experience”, leaving them emotionally exposed and more vulnerable to criticism. “I call it wearing your heart on your sleeve to work,” Dempsey says.

Speaking through art

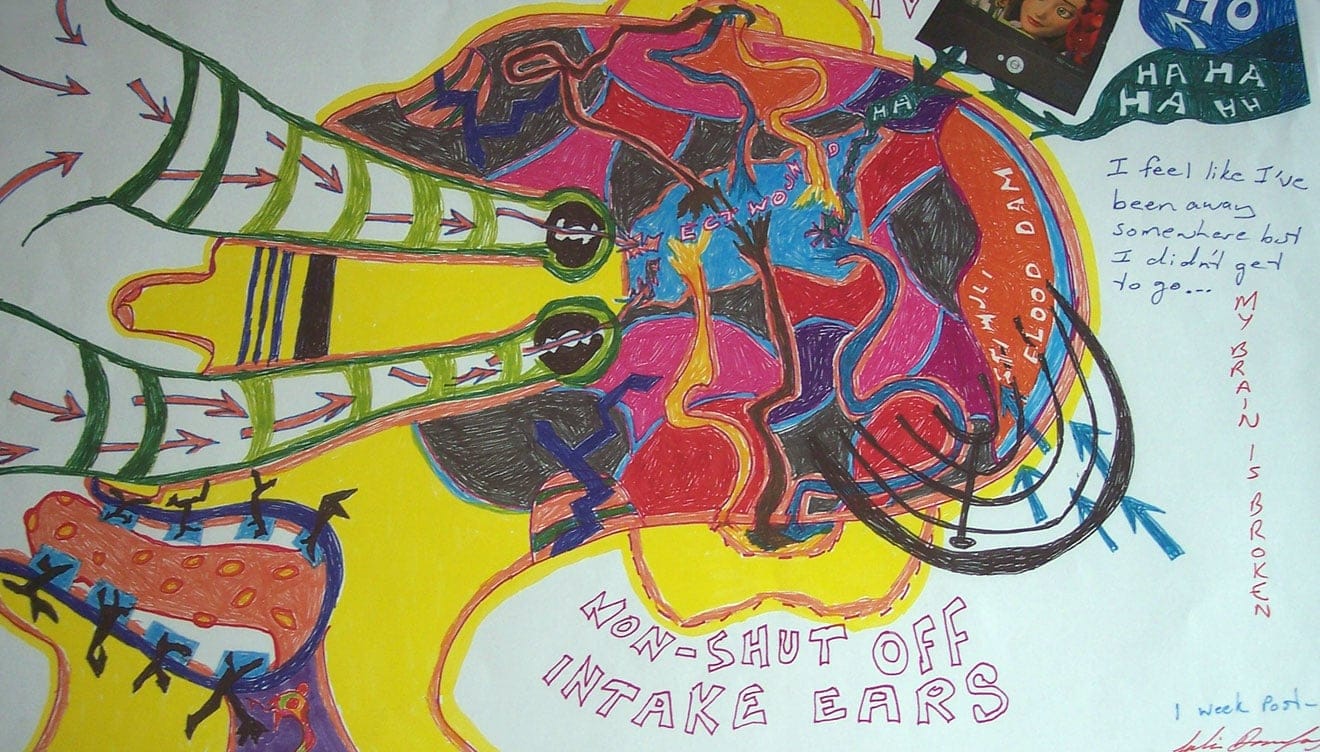

To cope with stress, Dempsey turns to art. “Being able to draw what is very hard to express” has been critical to her recovery – “a catharsis for getting out of my psychosis”.

And it also provides a window of understanding for others. Dempsey has taken her art to social work lectures at Monash University, inspiring a number of students to major in mental health after she explained mental illness through her pictures.

It’s a privilege, she says, to be back at her alma mater as a guest lecturer. As a student, Monash meant more than an education; the student counselling service was a beacon of support as she battled with her mental health and the medical system.

Her arts degree, earned over eight years, also provided valuable experience for her current role, which involves running training sessions and presentations, and writing submissions and convincing arguments for campaigns – including one for maintaining disability pensions for patients at Thomas Embling.

“I wouldn’t be able to operate at the level I do without those skills,” she says.

WATCH: The state of our mental health

More holistic and comprehensive mental health treatment programs are needed to tackle the rise in mental disorders. 'A Different Lens' documentary series asks the Monash experts what’s being done to improve mental health care.